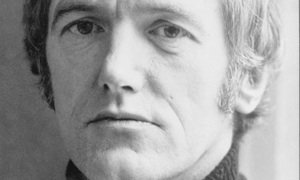

During his time abroad, which also included spells in Saigon, Washington and Tokyo, Frankland was twice named foreign correspondent of the year in the British Press Awards. But though he worked for the paper for more than 30 years, he remained an enigma to his Observer colleagues, who failed to penetrate the mysteries of his family background and his carefully protected personal life.

It was only after he had left that they learned through his memoir, Child of My Time, written when he was 65, that he was gay. What they did know was that Frankland was a diffident, modest man with a patrician accent and exquisite manners, all of which was fitting for a Carthusian descended, through his grandparents, from a barony (Zouche) created in 1308 and a baronetcy (Frankland) created in 1660. Curzons and Cromwell’s daughter also featured in his family tree.

Frederick Mark Frankland was born on April 18 1934 and brought up in aristocratic chaos at Castle Mead, a shambling old house belonging to his grandmother, Lady Zouche, on the edge of Windsor Park. His father, Roger, became a wing commander in the war and served at Bletchley Park. Mark’s parents were plainly unhappy and left their children to get on with things. They divorced while Mark and his elder brother Timothy were away at school. Mark’s mother’s second marriage also failed and she became an alcoholic. He said she was so discreet that she always bought her gin in half-bottles, from several different places, and hid them under cushions.

Perhaps because of this disruptive background, Frankland was a withdrawn figure — tall, thin, with penetrating eyes behind rimless glasses, giving little away about himself but inquiring eagerly about the people he was talking to. This was not only a useful quality for a journalist but also for a spy, which he became after reading History at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and completing a postgraduate course at Brown University, Rhode Island.

His knowledge of Russian, which he had learned during National Service with the Navy, marked him out to MI6, and Frankland was recruited after helping a Polish student escape to the West when he was attending a conference in Warsaw.

He was trained to pick locks, use codes and secret inks and eat messages written on special paper. He also learned how to fire a Browning automatic pistol and how to send signals from a beach to a submarine. In an exercise he failed to shake off pursuers who were tailing him, despite jumping on and off Underground carriages as the doors were about to close, as he had seen done in films.

Eventually, after working in MI6’s then headquarters in Broadway Buildings, he refused a posting to Africa and decided that the world of espionage, dealing in “boyish tricks and thuggery, stealth and deceit”, was not for him. He resigned after a year, which was virtually unheard of.

He had no training as a journalist before joining David Astor’s Observer in 1962 and had to be given lessons in newspaper writing by the veteran Soviet correspondent, Edward Crankshaw, himself a distinguished stylist. Astor encouraged his reporters to be innovative, and Frankland made his mark on the paper with an article based on hearing a Russian boy declaiming a Pushkin poem in the street.

But Frankland’s appearance in Moscow as a journalist raised eyebrows at MI6. They thought he might have been turned by the Russians if they knew of his intelligence background – as they might well have done, given that the traitor George Blake, who had worked in Broadway Buildings when Frankland was there, had compiled a list of British spies for his Kremlin masters.

On Frankland’s next visit to London, MI6 approached him and asked him to report on the Russians he was seeing. When he refused, he felt that a black mark had been placed against his name and he was given an uncomfortable grilling at the Ministry of Defence. He sensed he was being followed and that a watch was kept on his London house.

Despite this, when he was asked bluntly by a colleague in later years “Does one ever really leave MI6?”, he replied non-committally: “Now there’s a question.” In fact, as he explained in his memoir, he found himself caught in a curious espionage halfway house, not fully trusted by London, and certainly not by Moscow.

The Observer had fallen out of favour with Moscow by the early 1980s because of stories written by its political correspondent, Nora Beloff. As a result, Frankland was refused accreditation when he tried to return there in 1982. The editor, Donald Trelford, went to Russia to intercede on his behalf, only to be denied by an intransigent Kremlin official who put his head in his hands and muttered over and over again: “Observer, Nora Beloff, no, no no.”

Trelford then pointed out that one of his first acts as editor had been to dismiss Beloff from the paper. When this remark was translated and properly understood, the Kremlin apparatchik came round the desk with a beaming smile and enfolded the diminutive editor in a Russian bear hug.

So Frankland was allowed to return to the city, where his brand of scholarly analysis proved effective at illuminating readers about the Soviet Union’s impenetrable political system. Trelford, however, later wondered at the risk Frankland was taking in returning to Moscow as a former MI6 recruit and a homosexual. Had the paper been aware of these facts at the time, it might not have allowed him to go.

Frankland made a point of studying the language, history and culture of all the countries he reported on. He was profoundly affected by the war in Vietnam and later helped a Vietnamese family to settle in the West. The prosecution of the war left him with grave doubts about America, but he grew to love the country when The Observer sent him there. In Japan he learned the language and immersed himself in the country’s customs. In Czechoslovakia he became a friend of Vaclav Havel.

Apart from his memoir, and The Patriots’ Revolution, a book on the end of communist rule in Eastern Europe, he wrote Khruschev; The Sixth Continent; Freddie the Weaver (about his mother’s autistic adopted son); and two novels, The Mother-of-Pearl Men, set in Vietnam, and Richard Robertovich, set in Moscow.

Donald Trelford

(from The Telegraph –24/04/2012)

Mark Frankland was a handsome and clever young MI6 desk officer with an aristocratic pedigree who resigned from the service to become an award-winning foreign correspondent and the author of several good books. The most successful of these was Child of My Time: An Englishman’s Journey in a Divided World (1999), a frank and literary memoir that won Frankland, who has died aged 77, the PEN/Ackerley prize for autobiography.

As a correspondent in Moscow, Saigon and Washington, Frankland was able to view this divided world from both sides. During his 30 years with the Observer (1962-92), he reported on the two great pivotal events of the last quarter of the 20th century. In the spring of 1975, he witnessed the fall of Saigon and was on one of the last US Marine Corps helicopters to leave the South Vietnamese capital. Then, in 1989, he covered the uprisings in eastern Europe that marked the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war.

His reportage of the disintegrating Warsaw Pact became the basis of The Patriots’ Revolution – How Eastern Europe Toppled Communism and Won Its Freedom (1990). The book received accolades on both sides of the Atlantic. But when, nine years later, he published his tightly written and often elegiac memoir, the atmospheric detail supplied in his vignettes of life in Moscow and Saigon, particularly the louche underworld of Soviet Russia, was recognised as an absorbing and often iconoclastic read that went far beyond most contributions to the historiography of the cold war. “Frankland has a particular sympathy with outsiders and the betrayed. As a gay man in intolerant times and places, he knew he would never be on the side of the powerful, would always feel for underdogs,” wrote the transgender author Roz Kaveney.

Frankland was a direct descendant of the British diplomat, travel writer and expert on the Orthodox monasteries of the Levant, Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche, whose granddaughter married the Yorkshire baronet Sir Frederick Frankland. Family tradition saw to it that, a century later, young Frankland followed Curzon of the Levant to Charterhouse from where, in 1952, he obtained a major scholarship to study history at Pembroke College, Cambridge. But he did not go there immediately. University entrants could apply to have their two years’ national service in one of the armed services deferred, but the more adventurous seized the chance of a break between classroom and campus.

Frankland volunteered for the Royal Navy, where there was an appetite to train people with proven academic ability as Russian translators. He liked learning Russian, rapidly acquiring a working knowledge. And, as he revealed in his memoir, the navy provided the 18-year-old Frankland with a newfound opportunity for gay sex. This section rather startled some old friends. It was not that anybody doubted his sexuality, but he had always been discreet about it; neither proud nor ashamed to be gay. Just was.

After Cambridge and a postgraduate year in the US, he joined the Secret Intelligence Service, another family tradition. During the second world war, his father, Wing Commander Roger Frankland, a radio expert, had been attached to SIS’s crucial codebreaking unit at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire.

Basic training included a pistol-shooting course with Browning automatics: no fancy two-handed grips, but swivel on your left heel, point your weapon and give the target two bullets. Frankland soon concluded that the real point of all this was to engender a sense of mission and apartness. Reality was the commute to St James’s Park underground and his desk at Broadway Buildings, MI6’s headquarters until 1964, and it rapidly began to pall. He found the work tedious: he was given little opportunity to use his Russian, and the company was uninspiring. He began to pity the agents whose lives were in their hands.

After a year, he quit. He had decided to become a journalist and found employment on Time & Tide, an ailing but respectable political weekly whose contributors had included George Orwell. By 1962, he was on David Astor’s Observer and bound for Moscow. Unfortunately, so was another of Astor’s journalists. A KGB defector had at last provided all the necessary evidence to hang Kim Philby, who had fled Beirut, where, with MI6’s blessing, he had become Middle East correspondent for the Observer and the Economist.

Frankland had met Philby in the Broadway Buildings and he always suspected that Philby had identified him to the Russians, who would have probably shown him photographs of all the British residents in Moscow who might conceivably be working for MI6. There was a certain amount of harassment, but they did not throw him out. That happened in 1985 when, during his second and last stint in Moscow, he was expelled in retaliation for Britain’s expulsion of several alleged KGB residents in London.

In 1967, Frankland was transferred to Saigon. To his amazement, the SIS man at the British embassy there soon indicated that his old masters suspected that his five years in Moscow had resulted in him being turned by the KGB. Otherwise, they would have kicked him out, wouldn’t they? Nor did it help when, shortly after his arrival, Frankland scooped the resident press corps by interviewing a Viet Cong unit in a hamlet a risky hour’s drive away from the city. How could he have done it without special contacts provided by Hanoi’s Russian patrons? Answer: because the new correspondent had discovered that Mister Loc, the Observer’s office manager, was VC himself and understood the value of publicity.

MI6 was hopelessly wrong. Frankland had no sympathy for Moscow’s clients in Hanoi, and respected the fear and loathing so many South Vietnamese held for them. There were moments when he was disgusted by American behaviour. But by the time the war ended, he believed that by far the worst thing they had done was betray their Vietnamese allies by abandoning them to their fate.

Frankland went with them. The helicopter evacuation was a story in itself and another Observer reporter was staying behind to cover whatever followed. But there was another reason for his departure. He knew the men from the Soviet embassy in Hanoi would arrive shortly after the first North Vietnamese tanks and they would certainly have a file on him.

One of the last things he did before he left was give his Observer colleague most of his remaining US dollars. In later life, his conviction that the American withdrawal had been a great betrayal, the cause of thousands of unnecessary deaths as Vietnamese asylum seekers tried to flee Communist rule across the South China Sea, remained as firm as ever.

He entered into a civil partnership in 2006 with his long-time partner, Thuong Nguyen. He is survived by Thuong; his older brother, Timothy; his cousin, Diana Demarco; and three nephews, Nick, Mathew and Adam.

Colin Smith in the Guardian, 22 April 2011

Jonathan Fryer writes: Unlike most foreign correspondents – and indeed spies – Mark Frankland was the opposite of gregarious. He loathed big parties, and the idea of joining a London gentleman’s club, to which his pedigree and interests would have made him eminently suited, was anathema. The only “club” he ever felt comfortable in was the pub near the Observer’s old HQ known affectionately as “Auntie’s”.

I met Mark in the summer of 1972 in Tokyo, where I was studying Japanese and he was briefly posted; we were introduced by a young Japanese bartender who believed, correctly, that the dashing but eminently sensible British journalist could be a stabilising influence on his somewhat wild younger compatriot. Mark and I had a lot in common, not least spells covering the Vietnam war – to which he would later return – and he quickly assumed the role of honorary elder brother, which he would maintain faithfully for the next 40 years.

He had settled back in Britain by the time I moved to London in 1982 and he immediately arranged an entrée for me into the BBC. We would meet every few months for lunch, usually at a French restaurant, where we discussed politics, the media and world affairs, and he debriefed me about everything I had been getting up to in my personal life. He meanwhile arranged, with some difficulty, for his long-term Vietnamese partner, Thuong, to come to England, and the two of them were essentially home-birds.

In May 2006, Mark and Thuong entered into a civil partnership at a ceremony at Fulham registry office. The bubbly female registrar was surprised that there were only two other people invited, namely the two witnesses: the businessman Robin Hope, who had studied Russian with Mark in the navy, and me. This was typical of Mark’s sense of privacy and modesty, and, after the ceremony, the four of us walked down the road to a Thai restaurant for lunch.

Mark Frankland, journalist and author, was born on April 18, 1934. He died on April 12, 2012, aged 77