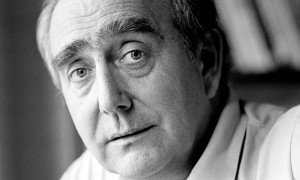

It’s not been a good time to say goodbye to fine people and Peter Corrigan, who had been ill for some little while with cancer, was among the finest you could ever wish to meet.

He was, as the BBC correctly observed on Friday, “a well-respected sports journalist”. But, as anyone on this newspaper who ever shared a pint, an anecdote or an argument with Peter will know, he was much more than that.

Hugh McIlvanney, who has recently retired, remarked once that it was easy to disagree with Peter, but impossible not to read what he had to say. He had that rare facility – identified by his brother Chris, who still works with us – of being funny in print. It was a priceless asset and much in evidence during his many happy years at the Observer, where he lit up all our Sundays with the most aptly named column in the business, Cyclops.

It wasn’t that Peter was one-eyed, it was more that the two eyes he brought to bear on any subject did not waver a split-inch from their target. He did not lack for conviction on just about any subject on which he was asked to pass judgment.

And that, of course, is what he was paid to do. He was a fine working journalist in the field, a great story-getting football writer and particularly fond of golf, but he was a born columnist who could shout above the storm with unmistakable clarity.

Peter was sports editor here for a while – in more relaxed times, it should be noted – and, once all the gubbins of the section had been ordered, put in place and prepared for consumption, he would rise towards the end of a Saturday afternoon shift and head for the door and back to Cardiff, stopping only to say to whoever was his deputy: “Take her into Heathrow, will you?”

It was away from work that he left an impression, also. When this newspaper was wandering around the capital like a lost lamb, we landed up for a while at Chelsea Bridge House and within a short evening stroll of a comfortable old pub whose ale went down all the better for the presence each Friday night of an old-fashioned rock’n’roll band.

It did come as a minor surprise one night, however, to see Peter jitter‑bugging his way around the bar with a pint in one hand and a younger female member of staff in the other, as if he were Elvis Presley brought to life.

That was his era, but Peter never seemed old and it is hard to believe he was 80 when he passed away. He was always up for a laugh, against himself or whoever deserved it more. I bumped into him at The Open at Sandwich a few years ago and noticed he was limping. He’d fallen in a ditch, he said. “Drink taken?” I asked. “Don’t be daft, man,” he said in that lovely Welsh lilt, “who falls in a ditch sober?”

As former colleagues reminisced about Peter on Friday, the memory that was most fixed was his boundless and indiscriminate decency. He treated everyone the same, with a smile that invited conversation, because that is what he loved as much as the job itself, a good old natter.

As his son, Jamie, the Telegraph’s golf correspondent, recalled, they were watching Wales play Slovakia in the European Championship last Saturday and, to the surprise of many, their team won 2-1. Peter, getting near the very end of his life, said: “Worth the wait,” and went back to sleep. It was, Jamie related, “a lovely, lovely moment”.

Those in the business who’d known him the longest echoed every kind sentiment that poured forth on social media. Norman Giller, a Fleet Street sage and author, called him “Peter The Great”.

Giller on his blog described him as, “a warm, witty and wonderful human being”, adding: “Peter will approve of the alliteration, because he was a master at plucking the golden phrases out of the air and ad-libbing them to the copytaker in the long-gone days of chasing hot‑metal deadlines and running reports.”

The deadlines will always be there; it is the methods of reaching them that have changed. But, for romance, getting on the old dog-and-bone was what Peter and others of that fading era lived for. It’s impossible to convey how much he will be missed by everyone lucky enough to have known him, from his days as a teenage messenger on the South Wales Echo, writing about football for the old Daily Herald, which morphed into the Sun, and through to the Independent on Sunday, after leaving the Observer in 1993.

All of the places he worked would no doubt imagine that theirs was his favourite. And he’d more than likely tell them all they were right.